All Humans of HBI

We want to understand how we learn from our mistakes. Recognizing what we did wrong is an essential part of learning – just imagine learning a new song, but without realizing you had played a wrong note. This is true not only for music, but for much of what we learn throughout our lives – from walking and talking to recognizing objects and faces. Our goal is to uncover how the brain detects errors and uses this information to guide learning.

I build "virtual model organisms” with artificial bodies and artificial brains that are trained to behave like real model organisms, such as insects and fish, in simulated worlds. The activity of these artificial brains can be studied in silico to help us understand how neural systems turn sensory information into decisions and complex natural behavior. Such "digital twin" models can complement real-world experiments that are challenging, expensive, or tedious – giving us a faster entry point to begin exploring the most promising hypotheses in the lab.

Our central nervous system has a very small capacity to regenerate. However, it has an amazing ability to rewire its circuits and adapt, whether after a traumatic injury or while we are learning a new skill. To study brain plasticity, I’m building autonomous AI systems that can help discover new patterns in complex behaviors and reveal which strategies of brain reorganization are most effective.

When you look at a neuron, the tiny cell body is just the tip of the iceberg. A tangle of branches called dendrites comprise a large volume of the neuron, acting like antenna for synaptic inputs. We do not fully understand how these long, thin, ion-channel-rich ‘noodles’ contribute to neural computation. I’m using optical imaging to explore this question, watching in real time the fast electrical signaling occurring in dendrites as they process information.

In the past, primary brain tumors were viewed as diseases that merely invade and destroy brain tissue. However, researchers now recognize that these tumors actually integrate into the brain’s circuitry as they grow and progress. Building on these insights, my research aims to uncover how brain tumors integrate into neural networks and influence cognitive processes such as learning and behavior.

Smoke, fresh-baked pie, rotten food, a floral cologne — at least once in your life (probably more), you’ve smelled one of these and tried to figure out where it came from. In each case, you can imagine an odor trace that travels through space and time until it reaches your nose, and your olfactory system detects it. But in natural environments, wind and other factors break up these odor traces (or “plumes,” as we call them) into signals that are sparse and highly fluctuating — nothing like the steady, delicious gradient of pie smell when you walk into a bakery. My work aims to understand how animals integrate this noisy odor information over time to figure out where an odor is coming from — and more specifically, which brain areas are involved, and how neurons in those areas weigh odor information to make these estimations.

I study how mammalian nervous systems evolved to generate complex movements like hand dexterity. I compare deer mice (the mice that are native to North America) from forests, which are good climbers and very dexterous, to those from prairies, which are not as good at climbing. I’ve found that the forest mice have a larger number of a specific type of neuron in their cortex. This is exciting because we think that evolutionary expansion of the cortex is important for humans’ skilled movement, like dexterous tool use, but we don’t really understand what having more neurons does for the brain. Our discovery about brain differences in the dexterous mice gives us a starting point for answering that question!

Mental health disorders are currently on the rise, especially among children and young people, and early life stress is an important contributor. A central question guiding my research is: Why do some individuals develop mental health conditions following early life stress, while others remain resilient? To explore this, I use mouse models to examine how stress impacts the brain across the lifespan. My goal is to identify the molecular mechanisms that drive vulnerability in some individuals and to discover ways to enhance resilience.

Neuromodulators, like dopamine and serotonin, are chemicals that are released throughout the brain in a coordinated fashion and are thought to serve specific roles, like dopamine in reward processing. Neuroscientists have historically studied these neuromodulators in isolation, but that is like listening to just a trombone to understand the symphony. Our brains are an ever-evolving mixture of these chemicals shaping and being shaped by the actual firing of our neurons. My thesis work aims to develop methods to measure multiple neuromodulators in concert with neural activity and use these tools to understand how neuromodulators interact to shape neural activity in both health and disease.

I study how the brain makes sense of what we see, using artificial neural networks and animal models. In both the brain and in visual neural networks, different areas can process different parts of visual scenes (one area processes edges, another colors, motion, etc.). In artificial neural networks, I study how these areas develop, learn and are robust to lesions, while in mouse and macaque models, I study how these areas interact and communicate with each other across different contexts.

I study perception. Specifically, I study input from the auditory and visual systems and how the brain uses its memories to influence what we see and hear. My research seeks to understand how our past experiences can change how our senses work and then alter our behavior. I want to understand how we interpret the world and what happens when our perception of the world fails.

Despite taking up 2% of body weight, the brain consumes 20% of the body’s energy stores at rest, and neurons have a very limited ability to store energy. When a part of the brain is active, blood vessels dilate in real time to deliver resources. Within the Gu lab, I am part of a team that studies how the brain regulates blood flow, on functional, cellular, and molecular levels. We use different imaging tools to watch this process unfold, which can ultimately give us insight into what happens when that balance is lost in diseases like stroke or dementia.

I study how the immune system and blood-clotting factors interact in gum disease. I work with genetically modified mice to understand the role of specific genes and analyze their tissues to see how immune cells behave in health versus disease. I try to figure out what’s going wrong so we can find better treatments!

People affected by psychiatric or neurological conditions, such as Major Depressive Disorder or Parkinson’s Disease, often experience severely reduced motivation to exert physical or mental effort toward a desired goal, which is thought to result from altered cost-benefit decision-making processes. In my work in the lab of Diego A. Pizzagalli, I aim to understand how exposure to acute and chronic stress or the presence of early-life adversity—factors often associated with the development or worsening of symptoms of psychopathology—impact the neural and cognitive mechanisms that guide motivated behavior in humans.

I study how the ear gets wired to receive sound information from the environment. During development, many different cells need to get to the right place and make stereotyped connections in a precise manner for us to be able to hear. My research examines how two of these cell types, neurons and glia, interact in wiring the cochlea, the organ of hearing. Understanding how cochlea wiring is established during development will provide useful insight for therapies to treat or prevent hearing loss.

In our bodies, the nervous system is the communication network, handling messages and quick decisions, while the immune system is the defense team, protecting us from invaders like bacteria. These two systems are constantly communicating and influencing the functions of each other, a concept termed “neuroimmune interactions”. In my work, I investigate the role of neuroimmune interactions in fighting bacterial infections in the inner ear, where our senses of hearing and balance originate.

I work in the admin office for the Neurobiology Department. In my job I wear a couple of hats. I do HR/onboarding, event planning/coordinating, and I assist with other general administrative functions of the department, including managing the communal rooms and department-wide communications.

We’ve evolved to avoid harm in dynamic and often stressful environments by rapidly altering the performance of key bodily functions. One important adaptation is in our hearing, where the auditory system must become more sensitive in times of need while also preventing itself from failure or being damaged. This is because sound, the very signal our ears detect, can be damaging when it is too loud for too long! My work aims to determine how the brain enables our auditory system to dynamically react to stressful signals in the world around us.

Graduate Student;

Herchel Smith & HHMI Gilliam Fellow

Lab of Beth Stevens,

Boston Children's Hospital

Herchel Smith & HHMI Gilliam Fellow

Lab of Beth Stevens,

Boston Children's Hospital

Imagine you’re decorating a house; as you decorate, each piece of furniture influences how you behave, and how they’re arranged influences how you interact with the whole. Now imagine instead that “you” are a cell in the brain, and the furniture is made up of proteins and sugars. What I study is how the furniture of the brain—those proteins and sugars—changes as an organism develops, and how that change influences how cells function, and how organisms behave.

I study how learning works in the brain. I draw inspiration from machine learning algorithms that are mathematically analogous to biological learning processes. Then I try to understand how elements of these learning algorithms can be implemented in biological hardware. My current work investigates how a machine learning algorithm called temporal difference learning may be accomplished through the interactions of multiple neurobiological parts: dopamine neurons, the neurons they release dopamine onto, and the intricate neural circuitry connecting them. I draw inspiration from theory but am mainly an experimentalist, working with mice and using the remarkable tools we now have to both control and record specific signals in their brains.

I’m interested in how very young animals, such as infants, experience the world and behave in it. We tend to think of infants as passive or undeveloped because they can’t do fancy things that adults do, like have an intellectual conversation. Yet infants have very particular ways of engaging with the world that are important for their survival and growth, and that are different from adults. I explore the infant-specific brain mechanisms that underlie these behaviors, using mouse models and combining tools from molecular and systems neuroscience. In the future, I plan to extend this work and look even earlier in development, at prenatal behaviors.

My work focuses on understanding how early life sensory experiences, especially tactile experiences, influence animal development. My approach to tackling this question has been to use mouse genetic tools to manipulate neuronal activity in touch sensory neurons during development and then assess the effects on the maturation of those cells, as well as on other cells and tissues they interact with.

I study how the brain’s dopamine system helps control movement. Dopamine’s effects on movement are usually thought to happen gradually, based on whether a behavior is rewarding or not. However, our lab has found that dopamine can influence movement almost instantly, with effects that last for a while. My research focuses on understanding the cellular mechanisms behind these fast, yet persistent, effects.

As people get older, they are more likely to get Alzheimer’s disease. Unfortunately, there are a lot of things happening at the same time so it can be hard to tell what is causing their problems. I’m trying to develop methods to watch individual cells in the brain as they get sick, so we can distinguish which features of the disease cause problems and which features arise coincidentally.

I am a neuroscience researcher studying dog brains. Specifically, I focus on how the presence of humans has influenced their brains. I aim to understand how dogs have managed to develop a way to comprehend our language, and how this could help us to better grasp how language emerged and evolved in humans.

I study how our brain transforms the light that hits our eyes into the rich and detailed images we use to understand the visual world around us. My research focuses on how different parts of the brain work together to recognize objects and their relationships in a scene, using techniques from psychology, computer science and neuroscience.

I study mechanisms by which neurons die in neurodegenerative disorders. In particular I’m interested in diseases where there are aberrant accumulations of a DNA and RNA-binding protein called TDP-43 protein – which include Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Frontotemporal Dementia, and Alzheimer’s Disease. In normal conditions TDP-43 is mostly present in the nuclei, but in these disorders it leaves the nuclei and so its function is disturbed. The recent discovery of a key target of this protein by our lab and others, Stathmin-2, has opened up the possibility of new biomarkers and therapeutics for these disorders.

When animals get an infection, they undergo a number of behavioral and physiologic changes – they lose their appetite, develop a fever, feel lethargic, and have diminished interest in social interaction. While infections are sensed by the immune system, these behavioral changes are generated by the brain. My work aims to link these two complex physiologic systems to define how the immune system communicates with the brain to change animal behavior during infection.

I study the fly brain. I am interested in how this tiny brain, itself smaller than some single brain cells in your cortex, can enable the insect to navigate through space. To answer this question, I record from brain cells in the animal while it behaves in a virtual reality environment that I can control.

Our lab focuses on characterizing the molecular mechanisms causing Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of motor neurons. Specifically, I’m involved in an effort to understand the role of STMN2, a protein decreased in the neurons of patients suffering from the disease. By defining the function of the protein, we hope to find new ways to treat ALS.

I’m fascinated by what makes individuals prone to mental illness. My current research explores the lifelong effects of early life adversity on susceptibility to psychopathology such as anxiety and depression. My goal is to find translational biological endpoints that can predict disease onset, inform early interventions, and ultimately prevent these disorders from occurring in the first place.

Not many PhD students, postdocs or other researchers have the time to learn and master every single technique required for a complex imaging experiment, so I do that. I am the expert in specific techniques and take care of parts of their experiments for them. Then I give them the results and they analyze it and get the data that they need.

I work to make STEM education more inclusive and equitable to support the success of all trainees. In my role I lead educational programs to promote diversity in STEM, I teach and mentor students ranging from high school through graduate and medical school, and I work with colleagues to establish policies and implement practices that promote equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging (EDIB) in the Harvard neuroscience and graduate education communities.

I study how the developing brain and social experiences interact in ways that increase risk for mental health problems during adolescence, a period of heightened vulnerability. Specifically, I examine how adolescents typically process social experiences, how differences in social processing can increase risk for mental health issues, and how we can leverage social factors to promote resilience in the face of social stress.

I study how humans learn and make decisions under limited cognitive resources, and how our brains allocate these resources to solve everyday problems.

I’m fascinated by how people learn to detect, interpret, and respond to threat in ways that are relevant to mental health. As a clinical psychologist and affective neuroscientist, I train both as a researcher and as a clinician.

I study how humans make predictions, or inferences, about unknowable or uncertain things, and how those inferences contribute to learning and decision-making. Some of the inferences that I'm interested in are our own feelings and internal cues, other people's feelings, and how much control we have over the world around us.

I’m passionate about increasing our understanding of how experiences of violence early in life, such as direct experiences of abuse or witnessing intrafamilial or community violence, impact brain development and ultimately, mental health outcomes. The overarching goal of our work is to shine a light on what’s happening “under the hood” after exposure to violence in childhood so that we can better tailor interventions to prevent or address mental health difficulties that follow.

Carlos Ponce just started a new position as Member of the Faculty at Harvard Medical School. His lab, which studies visual recognition, is moving here from Washington University in St. Louis. Ponce received his MD PhD degree from Harvard Medical School and his Bachelor of Science from the University of Utah. He is originally from Chihuahua, Mexico.

I study a super cool little tissue that most people haven’t heard of - at least I hadn’t until my senior year of college! It’s called the choroid plexus, and you actually have one suspended in each of the four cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled ventricles of your brain.

I’m fascinated by learning and decision-making. I study how neural activity in cortical areas changes while animals learn abstract associations during navigation. To do so, we use virtual reality, which is kind of like you're playing a video game in which you are working your way through a maze, and where you need to learn different rules to reach your goals through the maze. And I look at how cortical activity changes while animals are learning these rules.

I'm interested in understanding how the mammalian motor cortex and older subcortical circuits cooperate with each other to learn and execute complex motor skills.

I look at proteins that play a role in ALS-associated neurodegeneration. I'm specifically studying a nucleic acid binding protein called TDP-43. About 97% of ALS patients end up with TDP-43 in the cytoplasm of motor neurons when it's supposed to be in the nucleus. I’m trying to investigate the effects of this re-localization on motor neuron function and how other proteins might serve as ‘modifiers’ of this phenotype. In other words, I’m looking for other proteins and genes that may positively or negatively affect neurodegeneration in the context of TDP-43 disruption.

Serotonin and dopamine are widely known for their role in mood regulation, but these neurotransmitter systems also affect behaviors like learning and memory and homeostatic body processes like breathing and respiration. I study a subtype of serotonin-producing neuron that expresses a receptor for dopamine. This neuron subtype is involved in social and defensive behavior, and all evidence points to this being the only subtype of serotonin neuron to express any dopamine receptor in the mature mouse brain. Therefore, we think it’s an important link between the two neurotransmitter systems. My research has focused on what the purpose of this dopamine receptor is in relationship to behavior. I have found sex-specific changes in behavior when we delete this receptor from serotonin neurons, as well as sex differences in these neurons at the molecular, cellular, and circuit level.

Janine Zieg has served as Director of Research for the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School for eleven years, and overall has worked with department chair Mike Greenberg to support research activities in the Harvard neuro community for over twenty years—working in the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital before coming to HMS.

I study the relationship between brain circuits and brain stimulation therapies. This involves analyzing complex brain imaging data and pairing that up with brain stimulation data. A patient lying in a scanner may have their brain activity measured over about a thousand time points at about a million different spots in the brain. You end up with billion data points for every patient and it ends up becoming a data science challenge. The question then becomes how to integrate that with information about where a patient was incidentally stimulated and how they got better. Based on all that information, I develop models to try to figure out better ways to target our therapies.

I’m currently working on the gut-brain axis and oxidative stress during sleep deprivation with a great team of people from the Rogulja Lab. In addition to research, I love organizing conferences and special events – programs that bring together scientists across different countries, and that sometimes connect science with other aspects of society, such as sports or music.

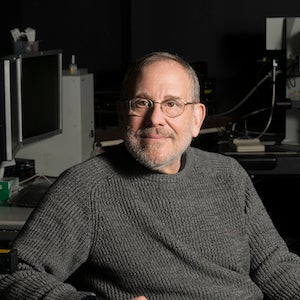

Joshua Sanes, PhD, is the Jeff C. Tarr Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Harvard University. Last month he completed a sixteen-year term as the Paul J. Finnegan Family Director of the Center for Brain Science (CBS) and a six-year term as co-director of the Harvard Brain Science Initiative (HBI). He has been with both CBS and HBI since their founding in 2004 and 2014, respectively.

Beth is a photographer who became a computer expert during the early days of digital photography. She has worked at Harvard for over 30 years, wearing many different hats. This March, Beth transitioned from the HMS IT Client Services Group to HMS IT Research Computing. A key part of her job is advising scientists about communicating with visual data.

I support collaboration amongst scholars, researchers and faculty. Currently, I am working with scientists at Harvard’s Center for Brain Science as Event Coordinator. I have been around the block at Harvard - over 25 years in Crimson service.

I study how memories alter behavior. What changes in our brain when we have an important experience—an experience that will affect how we behave in similar situations in the future?

The focus of my study is to pinpoint how the neurons in our ear acquire specialized features to reliably communicate auditory information from our cochlea—the hearing organ deep in our ear—up to the brain.

I study animal behavior. We sort of understand human behavior—when a human is angry or happy, what their gestures mean, and why they might do certain things.

My long-term goal is to understand how emotions are encoded in the brain. I’ve approached this question by asking how neural circuits orchestrate evolutionarily conserved social behaviors that are thought to be closely linked with emotions and how these circuits are modulated by sex, experience and physiological state.

I am studying how stressful early childhood experiences can alter the trajectory of brain development and predispose individuals to adverse mental health outcomes.

I am interested in understanding how neurons can write, update & store memories. This amazing capability of being stable & dynamic at the same time declines with aging and to a much further extent in Alzheimer’s disease. So, my research focuses on understanding how a healthy, adult brain writes & stores memories and how that changes in aging and Alzheimer’s disease.

I help people solve their imaging issues and find ways to move their science forward.

I am fascinated by how a single cell – the fertilized egg – gives rise to multicellular structures that are both highly complex and highly ordered. Over the past five years, I have studied this process using a tiny nematode called C. elegans.

I work in the Human Health & Performance Systems Group at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. My research focuses on auditory attention and the neural encoding of speech.

I’m a neuroscientist who studies how the brain regulates aggressive behavior. In my current project, I am identifying and characterizing the brain cells that activate female aggression.

I am an undergraduate student in my fourth year, majoring in computer science at American University of Armenia in Yerevan. This summer I’m working in the Dystonia and Speech Motor Control Lab at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

I work with neurobiology faculty across the Harvard Medical School Quadrangle to write collaborative grants for neuroscience research, in addition to writing about neuroscience research at Harvard for the general public.

I am the Security Officer at the Armenise-Goldenson building link at Harvard Medical School. I’ve worked at the University for 22 years. I was born in Puerto Rico and grew up in East Cambridge, MA.

I am building a machine learning model to identify genomic mutations in non-coding regions, which could have severe effects in various rare diseases. Even though 98% of the genome represents non-coding regions, our understanding of non-coding mutations remains very limited. I am using data science approach to tackle this problem, with a hope that it accelerates our understanding of the genetic cause of rare diseases.

I have an interest in neurodegenerative diseases and study the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) with an eye towards improving the delivery of therapeutic antibodies into the brain.

I am fascinated by sleep physiology and circadian biology. As a member of the Lichtman Lab, I have been reconstructing neurons from the master circadian brain clock (suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN) to explore their structure-activity relationship.