Imagine that you just met several people at a cocktail party, several of whom are wearing similar attire. You might quickly find yourself confusing two people you just met and calling them by the wrong names, all because your brain failed you in the process of assigning names to people. We often make mistakes like this when reasoning about our environment, many of which are the natural consequences of our cognitive limitations.

Using behavioral experiments and computational modeling, I study how humans learn and make decisions under limited cognitive resources, and how our brains allocate these resources to solve everyday problems. I’ve also become interested in how cognitive limitations can lead to more severe behavioral consequences such as belief rigidity, maladaptive habits like addiction, and psychiatric symptoms such as delusions. The hope is that by understanding how these mental processes arise in both health and disease, we could find ways to rehabilitate disordered behavior.

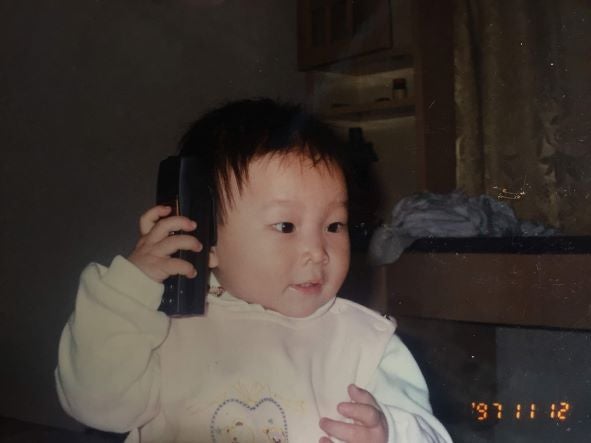

Photo courtesy of Celia Muto

Lucy as a toddler

Did you always want to be a scientist? Did you have a different career idea when you were a child?

The earliest childhood memory I have is from kindergarten, when I told my teacher that I, too, wanted to become a teacher. I think that conviction has never left me since. Even today, I feel the most alive when I’m teaching or mentoring.

I grew up as a creative and curious kid, always making things, writing fictional stories, and asking a lot of questions. I loved arts and crafts, making origami cranes and dragons and selling them to my classmates for $1 a pop (I should’ve charged more!). I also grew up playing the piano, and for a long time, wanted to become a classical pianist. In my late teens, I toyed with the idea of becoming an architect after spending over 100 hours in Google Sketchup creating a “dream house” for my eighth-grade geometry project. And there were books⸺I was always buried in library books.

In college, I discovered the field of cognitive science. It felt like the perfect way to combine my myriad of scattered interests in neuroscience, psychology, philosophy, math, and computer science. I became enamored with the mind and brain, wanting to understand the mental and neural processes underlying human reason and creativity. How did my brain so effortlessly translate notes on a page into finger movements on piano keys, or learn to memorize the fold sequence of origami art? How could I answer these questions using the language of computation and mathematics?

Thus my journey into science began and, together with my passion for teaching, launched me into academia. I now hope to become a professor one day, fostering the same kind of childhood creativity and curiosity in my students that I feel lucky to have never left behind.

Is there a teacher who made a big impact on your life?

My first piano teacher, Mrs. Diane Delk, was probably the most impactful teacher I’ve ever had. She taught me about music, and about life. I remember once asking her if I could play Chopin, because I knew other kids won piano competitions by playing Chopin. She smiled and hinted that my twelve-year-old self was too immature to emote Chopin properly in all his beautiful angst.

I loved playing the piano, but I was also lazy and hated practicing. So before high school, I quit. Sadly, that Christmas Mrs. Delk died abruptly of a brain aneurysm⸺I was devastated.

After her death, I committed myself back to the piano bench and started taking lessons again. This time, I learned Chopin and understood what she had meant. Mrs. Delk taught me that passion is not sufficient on its own, but that passion from the heart, plus hard work, can create a beautiful thing. Whenever I play the piano, I always think about Mrs. Diane Delk.

What traits do you admire most in other scientists?

I would have to say humility and kindness. There are a lot of brilliant scientists out there, but science also requires a lot of intellectual humility (to admit when you might be wrong) as well as kindness (for building a collegial and collaborative intellectual environment). I certainly chose my PhD advisor, Sam Gershman, for his intellectual prowess, but also because he is extraordinarily humble and kind.

What kinds of challenges have you experienced in your PhD?

A PhD is an incredibly challenging endeavor! I often tell people that I decided to pursue a PhD because I wanted to be humbled. There is a lot of failure involved⸺failed ideas, failed experiments, failing your advisor when you promised to finish something by a certain date but didn’t…the list goes on. One of the more “invisible” obstacles I’ve faced has been managing my lupus⸺a chronic autoimmune disease that can flare up when I’m stressed. But living with lupus has forced me to prioritize my health and work-life balance in a way that is sustainable, especially in a demanding work culture that academia often is. I think it’s so important for us to give each other grace in the workplace, especially because invisible illnesses such as my own, or those that relate to mental health, are so prevalent.

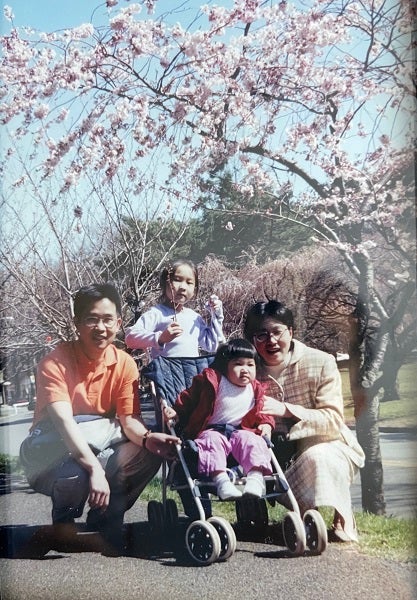

Lucy (standing), younger sister Sherry (in stroller), mom, and dad enjoying the cherry blossoms.

Who most inspires you and why?

Perhaps it’s cliché, but I would have to say my mom and dad. My parents left China in the 90s with two suitcases and a couple hundred dollars in cash. My dad, a cardiovascular surgeon, came here to do some research “for fun” and for a couple years, slaved under a ruthless PI who didn’t pay him a dime. It was only supposed to be a short trip, but my parents ended up staying for the next 27 years. My mother, also a doctor, effectively forfeited all her medical credentials when she immigrated, becoming a hostess at a local Chinese restaurant in order to help support our family. Though we didn’t have much in my early childhood, my mom always provided me with enriching learning experiences. She would bring me to the public library every week, instilling in me a love for reading that has followed me into adulthood.

My parents didn’t just create an intellectually nurturing environment to grow up in, but a spiritually rich one, too. These days, we spend many of our dinner conversations talking about theology and the role of faith in our lives and society. At the age of 50, my dad enrolled part-time in seminary, balancing heart surgery with countless nights of studying the Bible, church history, Hebrew and Greek. He inspires me to be a lifelong learner. We are currently on track to graduate together!

My mother, now a doctor again, spends every morning praying and reading the Bible before heading off to the clinic to serve her patients. She showed me that working mothers can be both gentle and nurturing at home, yet fierce and impactful at work.

What do you feel most passionately about?

Many people are surprised when they find out that I am a Christian. They wonder, how can a scientist, someone who believes in rational thought and the scientific method, also believe in God?

My short answer to that question is that faith⸺the conviction to act on a rationally-grounded, though still uncertain belief⸺is not confined to the realm of religion. In many ways, I view my faith in God as similar to the process of science: We have faith that our hypotheses are worth testing because they are rationally-grounded beliefs based on evidence from past scientific work. In the same way, I have faith that Jesus Christ is God, that he loves me, died for me, and rose from the dead to bring me into a relationship with him, because it is a rationally-grounded belief based on evidence from reliable historical accounts (many of which are secular), eyewitness testimonies, and stories of miraculous change in the lives of Christians past and present, including myself. This stands in contrast to what many would deem a blind faith, or faith in the absence of evidence. You can probably tell I am quite passionate about this distinction!

In the Biblical Book of Mark, a learned religious scholar asks Jesus what the greatest commandment is. Jesus responds: you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength; and the second is this: you shall love your neighbor as yourself.

Put simply, I feel most passionately about living out these two principles to the best of my ability, and that it is the ultimate purpose of my life. I see my faith as a journey enabling further exploration of who God is, how he has revealed himself in history, and how he is changing the hearts of people even today. My faith gives me unshakable peace in the complexities and trials of everyday life, because I trust in a God who unconditionally loves and cares for me.

Does your faith play a role in your DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) work? How?

It certainly does; I spend a lot of time thinking about ways to intentionally “love my neighbor.” One way this manifests is in my passion for helping people feel seen and cared for. That’s one reason I started Listening Labs with Jonah Pearl (a fellow grad student) in the Summer of 2020, in response to the deep turmoil going on in our nation and in our hearts. There’s so many important issues that we don’t normally talk about at work these days, and especially so in a culture where we tend to characterize people solely by their academic accomplishments. Jonah and I started Listening Labs as a vital space for people to share their stories and to discuss ways to cultivate a more equitable and inclusive culture at work.

Listening Labs events vary in format; some begin with individuals sharing their stories, and continue into a reflective discussion of ways to better care for each other. Others involve small-group discussions about concrete steps to take to make our lab environments more welcoming. Many felt that the forums increased empathy and awareness, and helped people feel safer and more connected within the department, especially during the pandemic. Through Listening Labs, I learned how to lead sensitive discussions with humility, and how to better listen and love those different from myself.

At the center of my motivation to love my neighbors is the desire to reflect the love with which God first loved me. Despite all the fallen and rotten examples of Christianity in society these days, I think that true Christians, who believe the words of Christ, should be deeply invested in conversations about race, justice, diversity, and inclusion, and to engage in them with humility and kindness, lest we forget the meaning of what the Old Testament prophet Micah said:

“…what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8)