By Daniel Hochbaum and Ralph Lawton

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis is known as an important regulator of metabolism throughout the body. In addition to this pivotal role, a growing body of evidence links dysregulation of thyroid levels to psychiatric symptoms. This effect on behavior suggests that thyroid hormone may directly or indirectly alter neural circuits in the brain.

Our recent work in mice revealed an adaptive role for thyroid level changes in animal behavior. We found that thyroid hormone levels in the brain coordinate exploratory behaviors with whole-body metabolic state by directly inducing circuit plasticity in cortex. This is important because in order for changes in behavior to be adapative, they must be coordinated not just with changes in the external environment, but also with the internal state of the organism.

Launching off of that insight in mice, we wanted to look at whether ‘normal’ variation (sub-clinical) of thyroid function in human populations correlates with any differences in people’s behavior. To do this, we used population-representative survey and laboratory data from the United States, from three waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

The HPT-axis comprises three key hormones that work in a cascade – TSH, T4, and T3. T3 is the primary, active hormone in the chain, binding thyroid receptors with high affinity throughout the body. Manipulating T3 levels led to the changes in cortical plasticity and exploratory behaviors that we observed in mice. However, human clinical practice measures, TSH and T4 as proxies for T3, largely due to ease of measurement, with the assumption that they accurately reflect T3 levels. We find that among individuals in the general population, TSH, T4, and T3 are only minimally correlated.

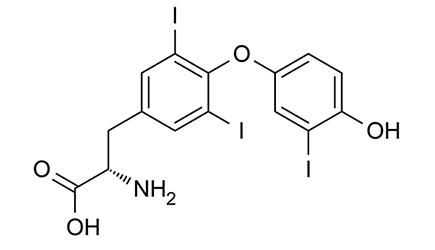

Illustration showing structure of Triiodothyronine or T3. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Next we asked whether there was information in T3 levels in humans that was missed by focusing on TSH and T4. We found T3 was linked much more strongly to demographic and socio-economic factors than T4 or TSH – we could explain 24% of variation in T3, but only 6-7% of the variation in T4 and TSH. For instance, we found that there is much larger variation of T3 levels with age. These results extended to longevity, for which T3 has a protective relationship (higher T3 associated with a lower likelihood of mortality) and T4 a negative relationship (higher T4 associated with a higher likelihood of mortality), with minimal links to TSH. Surprisingly, we found correlations to income and employment only with T3. Remarkably, we found that at older ages T3 levels are significantly linked to the probability of being employed, with higher T3 levels associated with a higher likelihood of working.

Our broad takeaways are twofold: first, our results emphasize the importance of directly measuring T3 alongside T4 and TSH, both for scientific discovery and for clinical practice. Second, our findings suggest that normal, sub-clinical variation in thyroid levels not only impacts bodily metabolism, but human behavior as well. Our future work looks to flesh this out more thoroughly – doing large-sample data collection of risk preferences and behavior alongside T3 measurement, to further pursue the population ramifications of sub-clinical thyroid variation for health and behavior.

Daniel Hochbaum is an Instructor in the Sabatini Lab, in the Department Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School.

Ralph Lawton is an MD/PhD student at Harvard Medical School.

Learn more in the original research article:

Longevity, demographic characteristics, and socio-economic status are linked to triiodothyronine levels in the general population

Lawton RI, Sabatini BL, Hochbaum DR.. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Jan 9;121(2):e2308652121. Epub 2024 Jan 4.

News Types: Community Stories