By Caroline Palavicino-Maggio

Eddie Rodriguez, Caroline Palavicino-Maggio, and Michael Mazzola sitting outside HMS

Imagine that the first experiment you’ve ever performed led to a publication in a high impact journal. Feelings of elation and accomplishment slowly creep into your mind as you simultaneously wrestle with the thoughts of disbelief. This is what happened to Michael Mazzola, a PhD candidate from the Division of Medical Sciences at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and the Chief Operating Officer at the Journal of Emerging Investigators (JEI), along with Eddie Rodriguez, Dean of Students at Somerville Public Schools, and myself in the early months 2019. We committed ourselves to enable and empower local Boston middle and high school students from historically underrepresented backgrounds in STEM1 to perform an independent research project while learning how scientists communicate through journal articles and how the scientific method can address community needs. This life-long dream of ours was a way of giving back to the community by allowing minority students to gain experience in the scientific peer-review process at a world-renowned institution. By partnering with JEI, a free, open-access science journal for middle and high school students, we created a unique program that would not only generate an inclusive community of STEM-focused students from underserved communities in the local Boston area, but also expose the students to various stages of scientific inquiry and methods. Our program included generating a hypothesis-driven experiment, guiding students on the required steps to successfully publish, and provided the students with an opportunity to publish at the conclusion of our program.

With over 200 graduate student and postdoctoral volunteers, JEI staff, such as Michael Mazzola, provided scientific peer reviewer feedback in addition to copy-editing, which supported young scientists’ communication and critical thinking skills. So far, JEI has published over 500 articles by young scientists from all over the world; 15% of these were generated by middle and high school students in Massachusetts.

We understand that writing a scientific article and providing data requires strict perseverance throughout the publication process, which is no easy feat. However, many institutions determine success by way of the number of scholarships published and by the caliber of journals in which they are published2. Therefore, introducing scientific communication and publishing to students early in their careers is highly beneficial, especially for underrepresented minorities, as this will consequently increase their retention rates in STEM careers3,4. We also recognized that strong mentorship from individuals who resemble the identities of students is critical to the success of underrepresented minorities5-7. Without this support, immersion in a strong scientific curriculum, and early scientific communication skill-building, even the most enthusiastic students lose confidence, feel isolated, and ultimately are less likely to continue pursuing STEM careers 3,4,7-10. Because of this, we aimed to create a unique program that would not only generate an inclusive community of middle and high school students, but that would also afford them an opportunity to become successful STEM researchers.

Knowing this task would have challenges, we fostered connections with Eddie Rodriguez to help market our program to the students and their families. When we contacted Eddie about the idea, it was envisioned as a sort of “camp”, where students not only attended lab meetings and shadowed PIs and postdoctoral fellows in the laboratories, but they also obtained a finished product by way of a publication. After several brainstorming sessions, we generated our program, the JEI Mini-PhD Camp.

“Education is still the civil rights battleground for students who have been historically disenfranchised. I sincerely believe that mentoring urban students, while providing Science programming that pushes students to the edge of their own limits, speaks to the effectiveness of the camp.

As a lifelong urban educator, I envision the programming as a tool for self-efficacy that could create a seismic shift in science education in urban districts and become a vehicle for true social reform.”

Eddie Rodriguez, Dean of Students of Somerville Public School District, and Director of Education and curriculum at JEI.

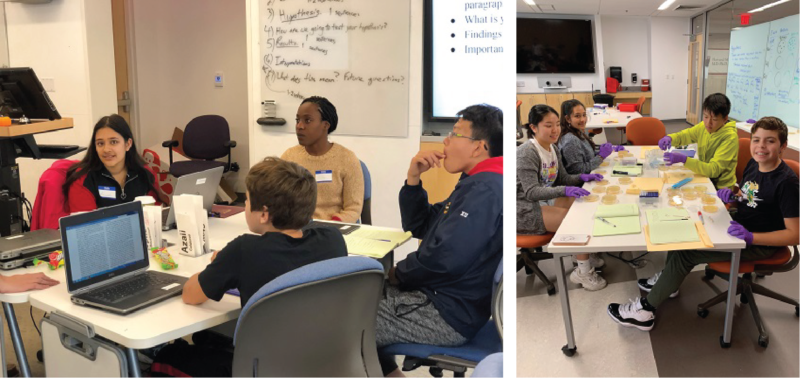

After a year of planning, the pilot program for the JEI Mini-PhD Camp commenced in  the fall of 2019 with 11 (from 8th, 9th, and 10th grade) students from middle and high schools located throughout the Boston area. Five Saturday sessions were held at HMS under the mentorship of 18 Harvard-affiliated volunteers. Additionally, students toured HMS microbiology labs, and interacted with a panel of minoritized scientists (specializing in astronomy, biology, health sciences, and math). Finally, recognizing that our students had diverse research and career interests, the camp paired each student with a JEI mentor who helped students design their own research projects, identify mentorship or outreach programs, and discuss how to prepare for college applications. As homework, students were tasked with developing their own scientific research questions and hypotheses in a professional lab notebook provided by HMS.

the fall of 2019 with 11 (from 8th, 9th, and 10th grade) students from middle and high schools located throughout the Boston area. Five Saturday sessions were held at HMS under the mentorship of 18 Harvard-affiliated volunteers. Additionally, students toured HMS microbiology labs, and interacted with a panel of minoritized scientists (specializing in astronomy, biology, health sciences, and math). Finally, recognizing that our students had diverse research and career interests, the camp paired each student with a JEI mentor who helped students design their own research projects, identify mentorship or outreach programs, and discuss how to prepare for college applications. As homework, students were tasked with developing their own scientific research questions and hypotheses in a professional lab notebook provided by HMS.

Throughout the five-week program, the high school students were methodically introduced to the concept of antibiotic resistant bacteria and were then tasked with hypothesizing which surfaces in their schools, homes, and communities were most likely to support antibiotic resistant bacterial growth. In teams of four, students were given supplies and encouraged to swab locations based on a narrative of their choice. One group decided to compare the surfaces of their school bathrooms, while another decided to swab foods at varying levels of processing (unwashed, washed, cooked, and rotten). They recorded their information onto a spreadsheet that compared quantitative and qualitative analysis of their observations and devised their conclusions based on this data. Having the students pull their conclusions together was another challenge, as it required asking research questions based on a particular scientific phenomenon. Furthermore, the students then summarized all of their efforts into written form and submitted it for publishing. After some polishing, undergoing scientific peer review, and then copy-editing, our students became published authors from the experiments they performed during the camp. In a post-program survey, 100% of students reported having increased confidence in their ability to identify methods and publish in JEI as scientists. The students also stated they would highly recommend the camp to their friends.

Although the second iteration of our camp was disrupted by COVID-19, Michael, Eddie, and I are planning to expand next year’s camp to include more high school students from the Boston area, and even include a virtual feature so we are able to expand our outreach. We decided to alter the research focus, introducing students to computational analysis and asking them to perform a neuroscience-based modeling experiment.

In addition to supporting the Mini-PhD Camp, JEI is currently partnering with Dana Farber’s Cure Program to extend their reach to other high school students interested in STEM careers. If you are interested in volunteering for CURE as a mentor, please sign up here. More information on mentoring can be found here.

Caroline Palavicino-Maggio is a research fellow in the laboratory of Ed Kravitz in the Harvard Medical School Department of Neurobiology. She is also the director of outreach at JEI. If you’d like to learn more visit www.emerginginvestigators.org/camp. To volunteer with JEI, fill out an application here: https://emerginginvestigators.org/prospective_staff.

Images courtesy of JEI

References

1. Racial and ethnic groups shown by the National Science Foundation to be underrepresented in health-related sciences on a national basis: Blacks or African Americans, Hispanics or Latinos, American Indians or Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders see http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/showpub.cfm?TopID=2&SubID=27) and the reportWomen, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering).

2. McGrail, M.R., Rickard, C.M., & Jones, R. (2006). Publish or perish: A systematic review of interventions to increase academic publication rates. Higher Education Research and Development, 25(1), 19-35.

3. Whittaker J.A. et al. (2015). Retention of Underrepresented Minority Faculty: Strategic Initiatives for Institutional Value Proposition Based on Perspectives from a Range of Academic Institutions. The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 13(3):A136-A145.

4. Daley, S., Wingard, D. L., & Reznik, V. (2006). Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(9), 1435.

5. David M. Marx and Phillip Atiba Goff, “Clearing the Air: The Effect of Experimenter Race on Target’s Test Performance and Subjective Experience,”British Journal of Social Psychology 44, no. 4 (2005): 645–57.

6. Sylvia Hurtado, “Linking Diversity and Educational Purpose: How Diversity Affects the Classroom Environment and Student Development,” inDiversity Challenged: Evidence on the Impact of Affirmative Action, ed. Gary Orfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2001): 187–203.

7. The science divide: Why do Latino and black students leave STEM majors at higher rates? The Washington Post. May 9, 2019.

8. Dong, Y.R. (1998). Non-native graduate students’ thesis/dissertation writing in science: Self-reports by students and their advisors from two U.S. institutions. English for Specific Purposes, 17(4), 369-390

9. Snyder, D. J., & Bunkers, S. J. (1994). Facilitators and barriers for minority students in master’s nursing programs. Journal of Professional Nursing, 10(3), 140-146.

10. Guilford, W.H. (2001). Teaching peer review and the process of scientific writing. Advances in Physiology Education, 25(3), 167-175.

News Types: Community Stories