By Shan H. Siddiqi, MD

We’ve known for over a century that different brain regions have different functions. Armed with this knowledge, clinicians started treating complex brain disorders by strategically burning focal lesions in specific brain regions. In recent years, we have seen the rise of noninvasive techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which enables us to easily stimulate different brain circuits. We commonly use this technique to treat depression by stimulating the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which is believed to be involved in emotion regulation.

However, our current treatment approaches lack precision. In most clinics, TMS is literally targeted using a tape measure and a Sharpie. This may seem crude, but it seems to work. We know that the DLPFC is broadly involved in depression, so we target somewhere in that broad region. We also know that the DLPFC is connected to underlying brain circuits that seem to be involved in treatment response. Some studies have used MRI-guided treatment to precisely target these circuits, but this hasn’t improved clinical outcomes. The problem is that we still don’t know how to target the right brain circuit for the right patient – even with precise MRI guidance, a “one-size-fits-all” approach may not be the answer.

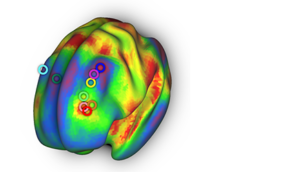

To address this, we started to think about whether certain treatment targets might be better for certain symptoms of depression. Fortunately, because of the “tape measure” targeting approach, most patients are stimulated at slightly different spots. Using brain MRI data in two independent cohorts of patients who received TMS for depression, we localized the spot where they were incidentally stimulated. Then, we mapped each of these spots to an underlying circuit using the “human connectome,” a large wiring diagram of brain connectivity based on functional MRI scans in 1000 healthy individuals. This showed us which circuit was stimulated in which patient.

By mapping the circuit that was stimulated in each patient, we were able to compare all of the patients to each other. We found something interesting. There were two overall circuits that mediated response to different symptoms. If a patient was incidentally stimulated at the first circuit, they saw improvement in “dysphoric” symptoms such as sadness and suicidality. If a patient was incidentally stimulated at the second circuit, they saw improvement in “anxiosomatic” symptoms such as irritability and insomnia. These findings were consistent in both independent cohorts. Taking it a step further, we also found that this explained variability in the published literature – studies that stimulated our “dysphoric” circuit reported more improvement in depression, while studies that stimulated our “anxiosomatic” circuit reported more improvement in anxiety.

If confirmed in a clinical trial, this will mark the first time that brain circuit mapping has directly improved clinical care. Furthermore, our approach is not limited to depression – we are now working to expand technique so that we can target any brain circuit for any brain disorder. We hope that this will usher in a new era of precision neuropsychiatry.

Shan H. Siddiqi, MD is an Instructor in Psychiatry in the Lab for Brain Network Imaging & Modulation at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

This story also appears in the HMS Neurobiology Department newsletter, The Action Potential.

Learn more in the original research article:

Distinct Symptom-Specific Treatment Targets for Circuit-Based Neuromodulation.

Siddiqi SH, Taylor SF, Cooke D, Pascual-Leone A, George MS, Fox MD.

Am J Psychiatry. 2020 May 1.

News Types: Community Stories