By Rick Born

Interpreting a negative result is always tricky—it’s a bit like the first sentence in Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina,” where a positive result is the one happy family and a negative result corresponds to the myriad, different unhappy ones. There are many ways to get it wrong. In our case, we trained monkeys on two different perceptual tasks that they learned to switch between. But to our surprise, when we recorded from neurons in the relevant regions of the monkeys’ brains, we failed to find the sorts of task-related neural signals that have been widely reported in the literature—including by us! So what went wrong? Nothing, probably. We had strong evidence that the animals learned both tasks and were, in fact, switching their perceptual strategies appropriately. We also had a lot of physiological and anatomical evidence that we were recording from the “right” neurons.

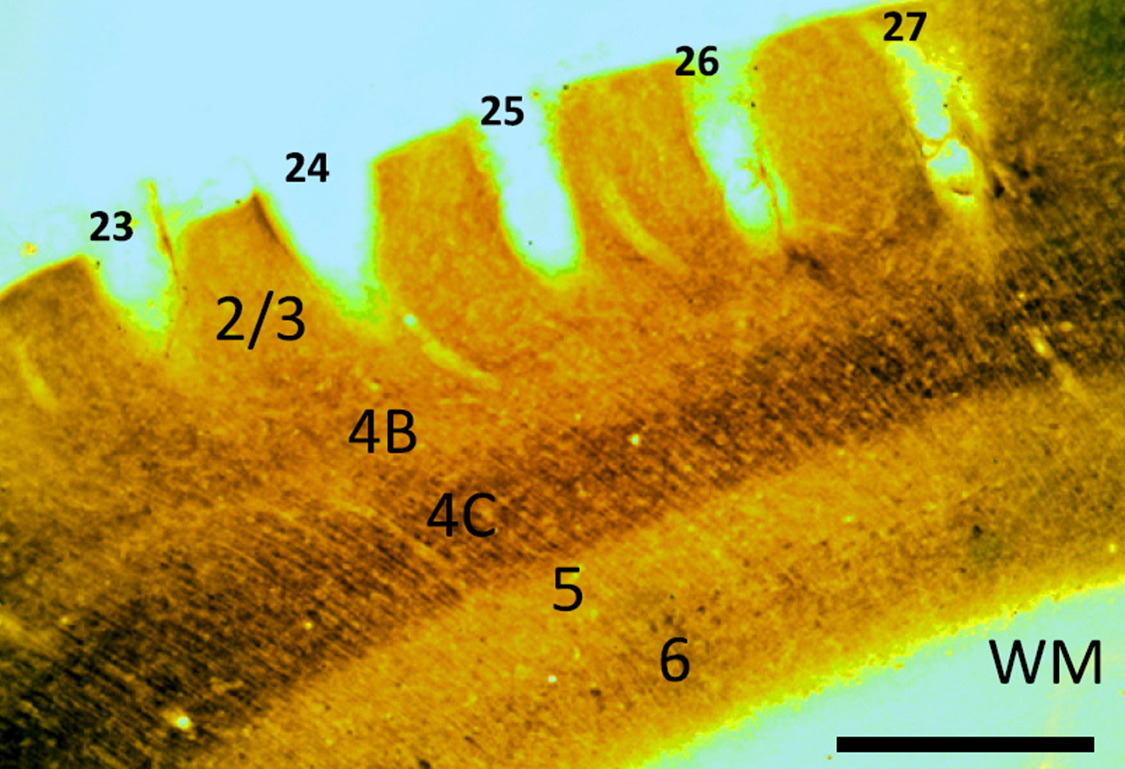

Ghosts of electrodes past. In this post-mortem section (stained for the enzyme cytochrome oxidase) through primary visual cortex of one of our experimental monkeys (“Urkel”), we see conical defects left by the multi-electrode array that allowed us to record from visual neurons for over 4 years. Small numbers indicate electrodes; large numbers show the cortical layers. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. Photo credit: Dr. Vladimir Berezovskii.

The major difference in our study was that the recordings were made during task learning and soon after the animals’ reached stable performance on the tasks. In most previous experiments, animals were trained for many months, sometimes years, on the same task before neural recordings were ever undertaken. While we can’t yet prove it, we think that many of the previous findings on choice-related signals in early sensory areas reflect a kind of “over learning” (more technically known as “perceptual learning”) that takes place in subjects over many thousands of repetitions of the same perceptual task, even after they can perform the task well. Thus our results raise the intriguing possibility that we, as a field, have been interpreting these neural signals incorrectly and that we need to pay closer attention to the exact training histories of our animals. Negative results from well designed experiments are important in that they force us to sit up and re-evaluate what we thought we knew. This is often not as intellectually satisfying as a positive result—we sometimes say that it just “muddies the waters.” But it’s beautiful mud!

Rick Born is a Professor in the Dept. of Neurobiology who was the co-senior author on this study. His lab performed the neurophysiology experiments and collaborated with the lab of computational neuroscientist, Dr. Ralf Haefner (Univ. of Rochester), on the design and analysis of the experiments.

Learn more in the original research article:

Lange RD, Gómez-Laberge C, Berezovskii VK, Pletenev A, Sherdil A, Hartmann T, Haefner RM, Born RT. Weak evidence for neural correlates of task-switching in macaque V1. J Neurophysiol. 2023 May 1;129(5):1021-1044.

News Types: Community Stories