By Lisa Traunmüller and Erin Duffy

When we enter a new place, our brain doesn’t just observe our surroundings—it encodes those experiences as memories. But how does the brain encode that new environment at the molecular level? This was the question that motivated our recent study.

Our brains are made up of billions of neurons that constantly communicate and change their connections with one another to encode and store memories. To do this, they rely on genes encoded in our DNA. However, while every cell in our body has the same DNA sequence, the identity of different cell types is dictated by which genes are turned on, or expressed, within that cell. Furthermore, the timing and levels of each gene’s expression are shaped steered by external cellular cues.

Neuroscientists have long known that sensory experiences can cause certain genes in neurons to change their expression. These sensory experiences encompass, for example, things we see, sounds we hear, or scents we smell. Despite this knowledge, we still had many unanswered questions: 1) how quickly do these changes in gene expression happen? 2) are they the same across different brain regions and cell types? And 3) which proteins bind to DNA to regulate the level of gene expression in response to the sensory experience?

We focused our study on the hippocampus, a brain region central to memory formation and learning about new spaces. Building on the idea that novel experiences trigger activity-dependent gene expression, we asked: How does exploration of a novel environment reshape the transcriptional landscape of hippocampal neurons, and how are these changes enabled by alterations in the accessibility of the DNA – that is the openness of chromatin that allows genes to be turned on or off? And finally, how rapidly are these molecular changes occurring when an animal explores a novel environment?

To answer this, we used cutting-edge sequencing technologies to measure both: which genes were turned on and how accessible the DNA was in different regions of the hippocampus after mice were briefly exposed to a new environment. Importantly, we looked at several parts of the hippocampus simultaneously — the dentate gyrus (DG), Cornu ammonis (CA)3, and CA1 — because these regions have different roles in learning and memory, and our sequencing methods allowed us to look at distinct cell types that play different roles in the brain circuit.

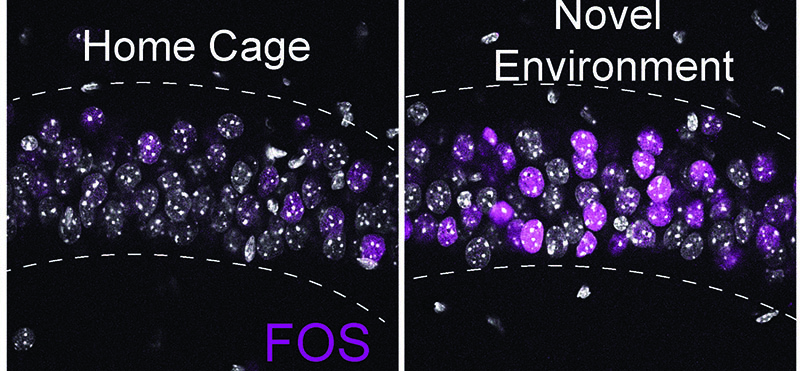

Novel environment exploration turns on new gene expression in the hippocampus, controlled in part by the activity-dependent transcription factor FOS, a well-known gene that rapidly responds to novel sensory experiences. Representative immunofluorescence image of FOS (magenta) protein levels in the CA1 region of the hippocampus from home cage (HC) and 90 min following a 30 min novel environment (NE) exposure. Gray indicates DAPI-stained nuclei.

What we found was striking. Even after a short exposure to a new space, thousands of genes changed their activity in highly region- and cell type-specific ways. Some genes were turned on quickly in one part of the hippocampus but not in others. We also saw that regions of the DNA became more accessible in precise patterns that matched the changes in gene activity. In other words, the brain is not just flipping a generic “learning” switch; it’s orchestrating a complex, finely tuned molecular response to new experiences.

We also discovered that the patterns of gene activity and DNA accessibility were different across cell types, where neurons and non-neuronal cells reacted in unique ways. Certain genes that were turned on after novel experiences are linked to signaling molecules and proteins that help neurons connect and communicate more effectively. This helps explain how short experiences can lead to lasting changes in brain function and gives us candidate molecules to follow up on in the future.

Why does this matter? Our work shows that the brain’s response to new experiences isn’t just a transient behavioral response. That experience is recorded by a change in the molecules of our brains, and it occurs within minutes of the experience. Understanding these mechanisms could help scientists understand how memories form and how experiences shape brain circuits. This is important not just for basic neuroscience, but also for conditions where these processes go awry, such as in aging, neurodevelopmental disorders, or memory loss.

Ultimately, this study gives us a richer picture of how the brain responds at a molecular level to the world around us and how we turn fleeting moments into long-term changes in neural circuitry.

Lisa Traunmüller and Erin Duffy are postdoctoral fellows in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Greenberg in the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School.

Learn more in the original research paper:

Novel environment exposure drives temporally defined and region-specific chromatin accessibility and gene expression changes in the hippocampus.

Traunmüller L, Duffy EE, Liu H, Sanalidou S, Krüttner S, Assad EG, Sun S, Pajarillo NS, Niu N, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. Nat Commun. 2025 Aug 21;16(1):7787. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-63029-6. PMID: 40841540; PMCID: PMC12370903.

News Types: Community Stories