I study a super cool little tissue that most people haven’t heard of – at least I hadn’t until my senior year of college! It’s called the choroid plexus, and you actually have one suspended in each of the four cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled ventricles of your brain. It consists of a sheet of epithelial cells that ensheaths peripheral blood vessels and thus, in addition to producing the cerebrospinal fluid, serves as a brain barrier structure between the body’s blood and the CSF. The choroid plexus has multiple other cell types, but my particular focus is on these epithelial cells.

Specifically, I research how these cells synthesize and secrete signaling factors into the CSF, like those that my PI (Dr. Maria Lehtinen) has found to be critical to proper cerebrocortical development. I am curious about the previously uncharacterized exocytotic mechanisms involved in this secretion, the targets of these factors, and their biological relevance.

Portrait photo by Celia Muto.

When did you know that you wanted to be a scientist?

I had a really unique situation in terms of choosing “what I wanted to be when I grew up”. After leaving home at 15 due to a difficult family situation, I found myself with utter independence and no external pressures imposing their career expectations on me. Sure, whatever I set my heart on doing, I had to figure out by myself, but I got to pick.

When I was 17, I came to the conclusion that before I started college, I wanted to be certain what I wanted to do in life. Did I even need to go to college? I thought it would be best not to waste that tuition money if not, and many life paths don’t need a bachelor’s degree. That year I worked as a manager at a Wendy’s. I moved around a lot at that time in my life, and didn’t really have many friends locally. I worked an average of 65 hours a week, which left ~70 hours of each week. Say I slept ~7 hours a night, that’s 21 free hours left of every week. What did I do with that time? I had always loved to read, and I decided that I was going to hone my life passions by reading. I’d head to the library every week or two and wander around the nonfiction section, taking home any book that sparked my interest. I ended up reading 300 books that year. I found that there were themes to the books that called to me, and these themes effectively convergently evolved to neuroscience. I was fascinated by behavioral economics, by genomics, and by psychiatric disorders and their treatment and perception. From this reading and from various life experiences, I became immensely frustrated with the current perception of and approach to treating psychiatric disorders, and actually for the lack of treatment for many neurological pathologies on a broader scale.

Then I read a book that gave me hope – “The Brain that Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science” by Dr. Norman Doidge. This collection of case studies was my introduction to neuroplasticity, and instilled in me the belief that neuroscience was a field that was poised atop a wave of discovery. It imbued in me hope that there was much to yet be discovered about the brain, and that these discoveries could be harnessed to help many hurting populations. In fact, I was so excited about this book, that as I read each chapter, I found myself at Wendy’s every day enthusing to my (admittedly less enthused) coworkers about it. “Paula!” I’d say, working the drive-through, to my dear coworker working the fry station “dude I have got to tell you about this woman who had this crazy balance disorder (central vestibular loss), like she couldn’t even stand up or walk or go through life, that got this tongue implant full of electrodes and rewired her brain to sense balance with her tongue!” If you’re curious, reader, Google “electrotactile vestibular substitution”. Paula was not curious, poor girl, but as I relayed different discoveries in neuroscience every day, I realized that I had fallen in love with a whole field. That book might have been the catalyst, but from there I chased many other books and sub-fields. I realized from popular nonfiction that the people conducting the actual primary research were all PhD scientists. I started reading primary journal articles in addition to these books, and concluded that I simply must be able to conduct this type of research myself. So here I am!

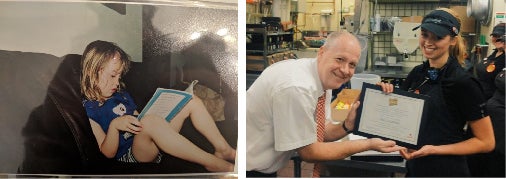

Left: Ya’el lost in a book as a child. Reading has been one of her passions lifelong.

Right: Ya’el working at Wendy’s before college, receiving a “Mop Bucket Attitude” award from the franchise owner for being willing to do even the grossest of tasks with a smile.

What is the most challenging part of your work?

I think many things about a career in academia are going to be challenging, and certainly many things about earning a PhD are challenging. I respect all who set about this challenge. I also have no doubt that many unforeseen obstacles are still ahead for me! That being said, for years I have looked forward to the relative ease of graduate school. Academia has long been gate-kept from a number of underprivileged populations – the Black community, Indigenous communities, Latinx communities, other racial and ethnic minorities, disabled communities, and the poor, among others. While I will never fully understand the struggles of many others who have hoped for and fought for entry into the STEM academic realm, I know how difficult it was for me, and I know how thankful and lucky I am to have made it this far.

I am one of the happiest, most content people I know. Life is really unbelievably good for me right now, but it took a lot to get here. I left a difficult family home at fifteen years old, so ten years ago now. My grand entrance into the independent adult world was made without money, without health insurance, without a car, without parents to go home to on the holidays or call in tough times. Those were a really hard couple of years. A lot of the people I met at that time – other troubled teens in foster care – are still struggling today. I wasn’t expected to make it this far. I had a temporary guardian tell me once that, the way she saw it, I had two paths left for me in life: “become a heroin-addicted prostitute on the streets or enlist in the military and maybe they’ll straighten you up”.

You can read more of my story getting here in this essay I’ve written, “Burgers, Bartending and Benchwork: My Journey to Graduate School”

Which teacher made the biggest impact on your life?

I have had many, many teachers and mentors who have changed my life for the better and whom I seek to emulate in various ways, but I’ll just pick one anecdote to share for now: Dr. Michael Bowman taught my high school AP Physics class. I took it junior year, but I actually switched into the class in early November. I had been attending a different high school for the months prior, where I was just enrolled in the base level high school physics course. When I moved schools, only AP Physics fit into my schedule, and I thought I was up for the challenge. After the first class period, I became nervous that I was a bit out of my depth, and after I got my first exam back with a 68%, I no longer thought I was up for the challenge. I had always found a lot of satisfaction in working hard in class, earning good grades, and in the approval of my teachers, and I had honestly never received a grade like that. Ashamed of myself, nervous about what this course grade would mean for my eventual college hopes and conditioned by society to be hyper-focused on getting straight A’s, I approached Dr. Bowman about extra credit. He gently refused to give me any opportunity for extra credit, and what he said next shaped the way I thought about learning, grades, and earning A’s from then on.

He asked me, “Do you like physics?”. I said “Yes”.

He said “Do you want to really understand it?” I said “Yes”.

He said “I picked the textbook for this course on purpose. It’s one of the most well-written textbooks I’ve ever encountered. If you read it, spend time with it, ponder it, do the exercises… If you seek to really understand the phenomena at play here and to develop an intuition for the first principles – you’ll never have to worry about the grades. The A’s will come. That’s true for everything, really”.

In the moment, I was frustrated. I thought there was no chance after that 68%. I rolled my eyes internally, my obstinate 16-year-old self might have even rolled them externally. In the months and then years that followed, I found myself less and less attached to any particular percent or letter grade. For the rest of that course, I fell in love with physics. I remember getting to the point just before the final where I ran the numbers and realized to my amusement if I got a 98% on the final, I would actually end the course with an A. I got a 100% on that final – not because I crammed, not because I studied to the test, but because I read that textbook cover to cover, I did all the practice problems, and I fell in love with the course. I found myself lost in the material, at times moved to tears when I saw the threads of a concept weave together and felt the joy and relief that the people who originally described a phenomenon must have felt.

This approach carried me with curiosity, tenacity, and grace through some of my later college coursework that I might have otherwise been worried about. I won’t pretend I read every textbook cover to cover – but some of them I did, and I did always seek to understand before I sought to perform on some evaluation. I look back fondly at how beautiful I found calculus, organic chemistry, and immunology, to name a few. Now, I can only try to impart that love of understanding over grades to the students I teach today. Thank you, Dr. Bowman.