Neuromodulators, like dopamine and serotonin, are chemicals that are released throughout the brain in a coordinated fashion and are thought to serve specific roles, like dopamine in reward processing. Neuroscientists have historically studied these neuromodulators in isolation, but that is like listening to just a trombone to understand the symphony. Our brains are an ever-evolving mixture of these chemicals shaping and being shaped by the actual firing of our neurons. My thesis work aims to develop methods to measure multiple neuromodulators in concert with neural activity and use these tools to understand how neuromodulators interact to shape neural activity in both health and disease.

Photo by Celia Muto

What are the big questions driving your research?

My work is driven by both basic science and translational goals. On the basic science side, I am interested in understanding how the brain undergoes discrete transitions in state when solving tasks. We can all relate to the experience of losing interest in a task, and I am interested in how the brain coordinates that shift from engagement to disengagement. Our hypothesis is that multiple distributed neuromodulatory systems drive this shift. I am developing methods to study multiple neuromodulators and neural activity simultaneously to test this hypothesis.

On the translational side, some psychiatric disease states, like depression and psychosis, have been proposed to be linked to changes in specific neuromodulators, like elevated dopamine driving psychosis. However, little work has actually measured this directly, and the success of non-specific drugs (e.g. drugs for psychosis that hit both dopamine and serotonin) in treating these diseases further challenges these simple theories. Therefore, the field urgently needs measurement of multiple neuromodulators and neural activity in disease models to test these theories. For example, it would be extremely informative to study how serotonin, dopamine, and neural activity all evolve throughout the onset of psychosis in a mouse model — something that’s never been observed. The methods I will develop in my thesis will hopefully allow such experiments, which can both deepen our understanding of disease biology and inspire new more tailored therapies.

What drew you to this area of neuroscience?

In college, I worked with child life specialists weekly at Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital. I ran their in-hospital radio station and TV studio that patients could actively participate in. I often interacted with patients undergoing long hospital stays for cancer therapy. Through their illness and stay, patients often developed comorbid psychiatric disorders, like depression and OCD. I was struck that oncology had advanced so rapidly in the past few decades that miracle drugs could save children from life-threatening cancer, but we could offer nothing new for their mental health struggles. For example, schizophrenia has had only one new class of medication approved in the last 30 years.

Because the brain is so complex, I strongly believe that we have significant basic science work to do before we can develop well-motivated mechanism-driven drugs for psychiatric diseases. Furthermore, I am confident that we are “undermeasuring” the brain and often working with an incomplete picture. Therefore, I am excited that my thesis project will help better track changes in brain molecules, cells and circuits in real time to discover its core physiology in both health and disease.

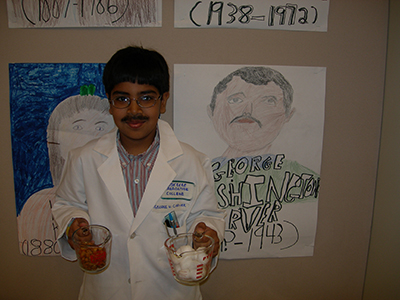

Akshay in the third grade dressed as George Washington Carver holding measuring cups with peanuts and cotton, two crops that Carver rotated to preserve soil health.

What is the first experiment you remember doing?

This isn’t exactly ‘an experiment,’ but, in the third grade, my class put on a ‘Great Moments in History’ day in which each of us pretended to be a historically significant person. While others picked presidents and generals, I chose to be George Washington Carver who developed crop rotation methods to prevent soil depletion in the American South. I was also excited that he popularized peanut butter! Through teaching my class about Carver’s life story, I learned from him that you could do science not just for your own curiosity but also to benefit others. A lesson I carry with me to this day!

What is an emerging area of science that you are excited about? Where you see potential for big discoveries in the next decade?

While my current work focuses on the interactions and roles of the ‘classical’ neuromodulators, dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine, there are hundreds if not thousands of lesser studied neuropeptides who have largely unknown effects on neural computations and mysterious roles in disease. Many labs, like the Andermann Lab here at Harvard Medical School, are now developing new tools to measure and manipulate these neuropeptides, and I anticipate a ton of exciting findings in this direction. From driving neural regrowth after a stroke to explaining how the brain tracks hunger, neuropeptides are likely underappreciated and important players throughout the brain!

Akshay performing a choreographed flip with his teammate during a team performance in his sophomore year of college.

Akshay performing as a DJ.

What are your hobbies outside of the lab—current, past, or future?

I have played soccer my whole life and continue to play intramural soccer on a team with my Program in Neuroscience (PiN) classmates. In college, I worked as a DJ at the Stanford radio station (KZSU). I am now a member of MIT’s radio station (WMBR) and recently had a show called the Spin Cycle! I love playing disco, house, and other dance music. I also occasionally DJ at parties and bars when the opportunity arises. Lastly, in college, I was on a nationally competitive Indian dance team that performed a traditional style of dance from the state of Gujarat called Garba Raas. I now continue to dance for fun, and you can catch me choreographing and performing at Indian weddings.