By Moira Dillon and Elizabeth Spelke

From the visual system to the seat of human memory to the systems that govern our reasoning and planning, the human brain is supremely sensitive to the geometry of our environment and the objects in it. How does this sensitivity emerge, and how does it support children’s learning and reasoning? To explore this question, we studied infants’ visual perception of simple 2D forms.

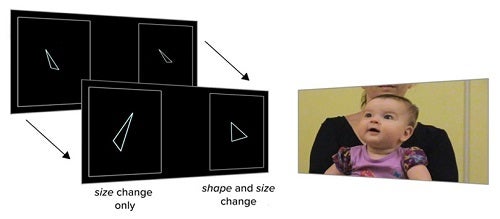

At around their 7-month birthday, infants visited Harvard’s Lab for Developmental Studies. Because infants at this age cannot yet tell us what shape differences they detect, we took advantage of their intrinsic interest in novelty and change: We measured how long they looked at simple, 2D triangles that either rapidly changed in size, orientation, and direction while maintaining their shape, or also changed in shape. We found that infants looked longer at the triangles that changed in shape, so we went on to ask what properties of shape infants care about. We removed one side of each triangle, and separately tested infants’ responses to two geometric properties: the relative lengths of the remaining two sides and the angle size of the remaining corner. We found that infants detected and were interested in the changes in relative length but not angle. Our findings suggest that as infants look around at the dynamic visual world, they perceive the shapes of objects by attending more to the relative lengths of their parts than to the angles at which different parts meet.

Seven-month-old infants watched two rapidly changing streams of visual forms, like these triangles, on a large screen in the lab. One on side of the screen, forms changed in shape and size, and on the other side of the screen, they changed in size alone. There were simultaneous, random changes in the forms’ positions, orientations, and – in some cases – facing directions.

Understanding more about infants’ geometric sensitivities will give us insight into how they (and we) perceive the world around us. The Spelke lab is exploring whether infants attend more to relative length than to angle because shape perception evolved to process the shapes of the objects that mattered most to our distant ancestors: the plants and animals that provide our food and also threaten us with poisoning or predation. Ongoing studies, conducted through Harvard’s remote video conference system, ask whether infants are especially interested in looking at moving displays with the shapes of plants and animals, and whether they can learn, from watching what others do and don’t touch and eat, whether a plant provides food that is safe or dangerous. Parents can sign up to participate in those studies here. The Dillon lab at NYU is exploring what such differences in attention to shape information might mean when children learn the names of objects or scenes or use drawings to communicate about objects and scenes to someone else. Parents can sign up to participate in those studies here. Both labs also are testing whether activities for preschool and primary school children, building on infants’ intuitive sensitivity to geometry, can enhance children’s spatial reasoning and their interest in learning mathematics in everyday life and in school.

Moira Dillon is currently an Assistant Professor of Psychology at NYU and is a former doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at Harvard. Elizabeth Spelke is the Marshall L. Berkman Professor of Psychology at Harvard. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CCF-1231216, DGE-1144152 and DRL-1348140) and the H2020 European Research Council (MathConstruction 263179).

Learn more in original research article:

Dillon MR, Izard V, Spelke ES. Infants’ sensitivity to shape changes in 2D visual forms. Infancy. 2020;25(5):618-639. doi:10.1111/infa.12343

News Types: Community Stories