A ‘reprogramming’ expert: From changing the identities of brain cells to changing science education internationally

A conversation with graduate student Mohammed Mostajo-Radji

October 11, 2016

October 11, 2016

by Parizad Bilimoria

Mohammed Mostajo-Radji can give a very compelling list of reasons why he’s doing the research he’s doing right now. But perhaps the most telling part of the response is this: “Because the books tell you you can’t.”

A graduate student in the Molecules, Cells & Organisms (MCO) Program at Harvard studying neurobiology in the lab of Paola Arlotta, Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, Mostajo-Radji is all about pushing the boundaries of possibility—in the lab, in the world of science outreach, sometimes even in ways that touch the distant realms of law and governmental policy.

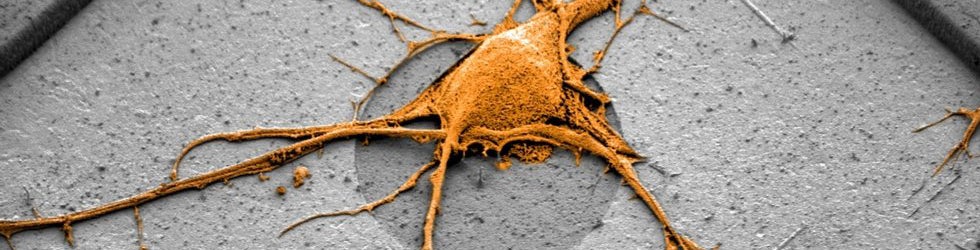

Mostajo-Radji’s current work focuses on neuronal cell identity in the cerebral cortex—the brain’s six-layered outer structure, the region which has expanded most rapidly throughout the course of evolution. “I am very interested in understanding what maintains neuronal identity throughout life,” he says. “Neurons are only generated—at least in the cortex—when you are an embryo and they remain with you for the entirety of your life. They are considered among the most stable cells in your body.”

The Arlotta lab likes to push these stable cells to change their identities, both to better understand the basic science of what makes one type of neuron different from another, and from the translational perspective, to see if unaffected neuronal types in neurological diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—in which very specific neuronal populations are targeted—can be reprogrammed to take over the duties of neurons that are degenerating or dead.

For a long time it was unclear whether altering neuronal identity was at all feasible. But in 2013, Arlotta and postdoctoral fellow Caroline Rouaux demonstrated that it was indeed possible to change neuronal identity within the the brains of living mice. Specifically, the two transformed callosal projection neurons which carry information between the two hemispheres of the cerebral cortex, into cortifugal neurons which carry information out of the cortex. This was particularly exciting because the corticofugal category includes corticospinal neurons which control limb and body movement by carrying information from the cortex to the spinal cord and are one of the two key motor neuron populations afflicted in ALS.

“Neurons are social individuals. They like to be connected.”

The identity change was accomplished by turning on the expression of a powerful transcription factor called Fezf2—a molecule that controls the activities of many genes related to the corticospinal neuron identity. The next question was what such ‘re-programming’ of individual neurons meant for neural circuits and their function.

“Neurons are social individuals. They like to be connected,” Mostajo-Radji says. “So if their partners don’t change, then it’s almost useless to reprogram them.”

In a recent collaborative study with graduate student Zhanlei Ye in the lab of Takao Hensch, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology, and others, Mostajo-Radji studied in more depth the Fezf2-controlled callosal to cortifugal neuron identity switch and learned that circuits can actively re-wire in response to the re-programming of individual neurons in their midst. In other words, the changed neurons aren’t just different on the inside—their new identity is recognized externally, with other neurons adjusting how they communicate with the reprogrammed neurons to match their new identities.

“Not only do we know that we can change the identity of these neurons, but now we show that the circuit adapts to this change,” Mostajo-Radji explains. Already these results are providing new insights into the principles governing neural circuit wiring.

Changing mindsets

Mostajo-Radji’s presence in a science PhD program is in itself an example of his tendancy to push boundaries. He was born and raised in Bolivia, where, as he puts it, “Science wasn’t much of an option.” The country does not yet have PhD programs in the natural sciences with the exception of one program in physics. And while medical training is available, there aren’t many undergraduate degree programs in pure science.

But none ot that stopped Mostajo-Radji who as a high school student was admitted to the National Youth Science Camp—a highly competitive, all expenses paid one-month long summer science program held in the mountains of West Virginia about 4,000 miles from his home. The National Youth Science Camp admits only two students from each U.S. state and a small handful from other countries. Mostajo-Radji was one of 3 students from Bolivia in the summer of 2006.

Mostajo-Radji (right) as a high school student, at the National Youth Science Camp in West Virginia, Summer 2006.

“I will be forever thankful to the US Embassy in Bolivia,” he says. “By sending me to this program, they changed my life.”

At the camp he met D. Holmes Morton, co-founder of the Clinic for Special Children in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, who was studying the genetics of a rare form of the brain disorder microcephaly in Amish children. “He became my idol immediately,” Mostajo-Radji says. ‘This is what I want to do. This is my life goal,’ he remembers thinking about biomedical research.

As soon as he got back home from the science camp, he set out to investigate the admissions process for undergraduate science programs abroad, and soon after ended up back in the U.S., this time at the Rochester Institute of Technology. There he majored in biotechnology, minored in science policy, served as a residence advisor and worked in two different labs on human genetics projects. In addition he spent a summer at UCSD,where he worked in the lab of Nobel Prize winner Roger Tsien on a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging project.

But it wasn’t just research that Mostajo-Radji had fallen in love with when he met Dr. Morton at the science camp. For Morton is no ordinary scientist. The MacArthur foundation describes him as “a unique amalgam of country doctor and research physician” and the New York Times, in a story highlighting his deep impact on the medically underserved Amish and Mennonite communities, notes that his clinic is “probably the only place in the country with a mass spectrometer inside and a hitching post outside.”

That ability to work across professions—embracing interdisciplinary learning and bringing together radically different worlds for the sake of science—is something that made Morton a particularly compelling role model. And Mostajo-Radji is already emulating. When he started graduate school at Harvard he took advantage of the ability to cross-enroll in different schools of the university and took some courses in the Harvard Business School, as well as the Harvard Kennedy School. Combining some of what he learned there with the scienitifc training from his PhD program, he has already worked with colleagues at Harvard and other institutions to launch an international science outreach venture, Clubes de Ciencia Bolivia.

The Bolivian program is part of a larger initiative that began with Clubes de Ciencia México three years ago, and also has a Colombian counterpart. Mostajo-Radji leads the Bolivian program and serves as an instructor in the other two programs.

The general idea of Clubes de Ciencia is to bring U.S. graduate students and postdoctoral fellows to Latin American countries to run weeklong outreach programs so that more international students can be served than when the outreach programs are located soley in the U.S. Additionally, Clubes de Ciencia promotes parternships between U.S. universities and Latin American universities—connecting instructors from the U.S. with co-instructors in Mexico, Colombia and Bolivia so that the outreach impact lasts much longer than the official week of the program. Currently the community of instructors and co-instructors across all four countries is about 300 strong.

“My team wants to bring two topics to the table: The first one is that Latin America needs more science if it wants to grow economically, and the second is that the secret is trusting the younger generations. We have the potential. It is a matter of utilizing it.”

In its first year, the program in Mexico served about 100 students in one city. Now, the Mexico program serves an average of over 700 students in six cities total. The Colombia and Bolivia programs started just this past year and are also rapidly expanding. Each weeklong program features a 40-hour intensive, hands-on research course custom-designed by the instructors and centered around a theme of current scientific interest. For example, next January Mostajo-Radji will lead a course called “Changing the Brain’s Mind: Principles of Brain Manipulation” featuring some of what he has learned about reprogramming neurons.

In less than a half year after the first session in Bolivia, Mostajo-Radji sees clear positive outcomes beyond the learning accomplished during the program itself. “It’s very exciting,” he says. “We have at least 10 stories of kids who have done really, really well already.” For instance, two participants are traveling this summer to Peru to work on a collaborative research project between Johns Hopkins University and Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru. Additionally, a student who had taught himself how to program and build robots was able to gain a full scholarship for college at the Catholic University of Bolivia (a sponsor of Clubes de Ciencia), and another student is working on the first nanosatellite completely built in Bolivia.

“A major challenge is changing the mentality,” Mostajo-Radji explains, noting that students in Bolivia are often not used to seeing science as a real career possibility. He and his colleagues are seeking local and foreign governmental support to help overcome this public awareness challenge, as well as to potentially gain the funding needed to serve larger populations of students. To work towards this, he is taking a creative and multi-pronged approach, partnering with friends in marketing professions to make videos, connect to news outlets and launch several social media campaigns.

“My team wants to bring two topics to the table: The first one is that Latin America needs more science if it wants to grow economically, and the second is that the secret is trusting the younger generations,” he says. “We have the potential. It is a matter of utilizing it.”

Aiming sky high

Mostajo-Radji’s interest in changing mindsets reaches well beyond the frontiers of science education. While the Youth National Science Camp he attended in the U.S. was a powerful motivator drawing him to biomedical research, much of Mostajo-Radji’s love of research can be traced back even earlier, to social science work he started as a high school student with his aunt, a gynecologist who at the time co-directed the Center for Investigation, Prevention and Treatment of Sexual Abuse in Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Some of the research he helped her with there, such as analyzing data on sex abuse incidents and contributing factors, has led to real policy changes. “The Center focused on girls under the age of 16, which is a particularly vulnerable group. I was a teenager at the time, so I was immediately struck by the stories.”

“For me it was extremely gratifying to see that we were able to go from the data to actually proposing new laws. Now in Bolivia, for example, the police department has a section specifically for victims of sexual abuse. We believe we were a very big contributor to this,” he notes.

He adds that Bolivia has consistently been ranked as the country with the highest incidece of domestic violence in Latin America. However, it became one of the first countries in South America to begin prosecuting legal partners for sexual abuse. “It was unheard of in that region… That was a direct effect of that institute. That’s what got me really excited about research.”

“I am really, really supported—by my PhD advisor, the graduate program and Harvard in general—to explore different career possibilities as a student.”

Soon Mostajo-Radji will be moving to the next stage in his research career—postdoctoral work focused on the specification and maintenance of human neuronal identity. After establishing himself as an academic scientist, he hopes to become deeply involved in shaping science policy, perhaps around science education and the inclusion of traditionally underrepresented groups in the sciences. “My dream is to see South America exploiting the resources that it has, both human capital, as well as the biodiversity of the region. I can think of so many interesting questions that can be answered – particularly in evolutionary biology – if we just had a better appreciation for the pure sciences.”

Mostajo-Radji feels nurtured by the MCO graduate program and encouraged by the Arlotta lab to explore the bigger picture surrounding his work and think broadly about career opportunities. “Honestly, when I came into the program I didn’t expect this level of support. I am really, really supported—by my PhD advisor, the graduate program and Harvard in general—to explore different career possibilities as a student,” he says. “That’s something I always say is probably the best thing at Harvard. You have the opportunity to get input from industry, the business school, the law school, the government school… You can re-shape what you want to do, even if you didn’t know it when you came in.”

So what does Mostajo-Radji do to unwind, when he’s not working in the lab, taking courses, or traveling to Latin America to teach? In a fitting response from someone whose ambitions run sky high, he says, “My hobby is airplanes. I come from a family of pilots. I’m hoping to one day get a license to fly one.”